There’s no such thing as humane slaughter; it’s not humane nor ethical to kill an animal that doesn’t want to die.

I ask you to ponder this, then: Is it really immoral to kill an animal, or is it more immoral to not kill an animal? Is humane slaughter truly a myth, or is it?

The answers may (or may not) surprise you.

This has been probably the most difficult blog post I’ve ever forced myself to write. It’s not a comfortable thing for us humans to be talking about death, and I’m certainly no exception. Doing so gives light to the uncomfortable truth of our own mortality; none of us will ever live forever.

But it’s a topic that still merits some discussion, particularly when it surrounds the highly polarizing topic of whether we should or should not be killing animals for food. And because this entire site, let alone this blog, is pretty much everything to do with raising animals for food, death is a topic that can’t be ignored. Not especially when it involves the farmers and butchers who participate in the whole “Circle of Life” from birth to death; from turning a live animal into a very nutritious source of nourishment for our bodies. And not especially when the purpose of this site, and this blog, is in support of such people, and the very existence of such a system.

The main reason I’m purposely making this a rather lengthy introduction, and why I’m even pursuing such a topic—yet again—is because I find it gets brought up repeatedly by vegans, animal rights activists, virtually anyone who is fundamentally and religiously opposed to killing animals for food and is purposefully directed towards anyone who willingly participates in the consumption of animal products, including myself.

The context in which it gets brought up is where such people are vigorously on a mission to “educate” the masses on where their food comes from; how most animals actually get to their plate. The means of doing so is through shock-and-awe, fear- and guilt-tripping tactics, victim-blaming, the works. Unfortunately, the “facts” that these fanatics openly share with anyone who will listen or read them are based on half-truths as well as deliberate misconceptions and misinterpretations of what happens to a chicken or a cow that goes from the farm to peoples’ plates.

The reality is that most people in the world live in an urban setting and are several generations removed from the farm. Many truly have no idea where their food comes from, from your average soccer mom to the CEO making big bucks in that high-rise building several blocks away. I will agree with a lot of vegans that most people who eat an omnivorous diet really don’t know how that package of ribeye got to the grocery store shelf, and what had to be involved in order for it to even get there. With 98% of the population living with such circumstances, that’s saying something.

That leads me into another point: Most people are so far removed from the farm that they are also wholly separated from the aspects of life and death; virtually they have no, or a very poor comprehension and understanding of the Circle of Life, other than what they get from Disney movies like Bambi or The Lion King, or BBC (or Discovery’s Animal Planet) nature shows on television. Very, very few have ever truly experienced or seen first-hand the things involved with Death and Life. A television program or movie that has undergone significant editing never serves justice to what happens in real life. Having a pet doesn’t do justice either. Most pets are treated like furry four-legged (or feathered two-legged) humans, not as actual animals that they are.

Anthropomorphism is applying human thoughts and emotions to animal behaviour. It’s a very prevalent and powerful force that plays a huge role in how animal activists get people to relate to animals and turn them against raising animals for food. The reason that this can be done, and is actually so easy to do, is because most people just don’t know how else to relate or understand how a cow, a chicken, or a pig even thinks or behaves; they only way they can even try to understand animals is to apply human characteristics, emotions and thoughts to them.

When it comes down to killing animals for food, I think you can see now how polarizing this topic can get in discussions. Let me bring an example to light: Remember when I wrote the article on the video “Saddest Slaughter Footage Ever”? Well, let me put it in this rationale.

Those who don’t know what they don’t know about what is going through a bovine’s mind up to the moments a cap-bolt gun is placed in the middle of his forehead, and can only relate to that bovine through human emotions and thoughts, are so convinced that that bovine is scared shitless of dying and really doesn’t want to die. Hence their rhetorical mantra to the masses: “Why do you want to kill [something/someone] [who/that] doesn’t want to die?” On the other hand, the few of us (including myself) who have spent quite a bit of time around bovines and are able to see well past the myth that they’re slow, gentle, kind, and rather dumb creatures, are able to see, through the way that steer is reacting that he’s not scared at all; just a little nervous at being at an unfamiliar place with unfamiliar sights and sounds. He really has no idea that he’s about to die so that his body can go to feed hundreds of people and other animals. These few of us also understand that he may not want to die, but he has no choice in how or when he will go.

Therein lies the conundrum. No living thing wants to die, but no living thing was designed to live forever, either. Thus, every organism that is alive will die; the question is how they will die, and when.

Until someone comes up with some magical elixir where everyone and everything will live forever, this is an ultimate, inescapable fact of life. This fact is one that is so very difficult to explain to those who just don’t know, and who weren’t raised in the same way nor exposed to the same things that the few people I mentioned above, have. It’s particularly tough to explain such concepts to those who are so fundamentally opposed to animals having to die so we can eat. Those are the type that isn’t worth the time since they’ve convinced themselves so intently that they’re right about what they believe that it’s impossible to help them to understand an entirely different perspective than they may fundamentally disagree with.

This blog, as I hope you may have guessed, isn’t directed at such people. It’s for those who are still on the fence about animal deaths, and still, need to know more to know which side of the fence they need to jump off from.

My effort here, also, is to show you how these rather, “anti-death crusaders” may completely miss out on the understanding that we have a moral responsibility to not only give the animals in our care the best life possible, but also the best death possible; one that is quick, painless, and certainly humane. My intention is to also show how and why these people may in fact be contributing to animal abuse and cruelty in more ways than they realize.

My Writings Prior To…

Prior to this post, I wrote a couple of articles on this very subject: Graze ‘Em and Eat ‘Em; and “Needless” Slaughter? Not So.

I primarily concerned myself with arguing for the merits of carrying capacity of the land: Feeds and forages are a finite yet renewable resource, thus control measures for a herd or flock’s prolific mating habits must be in place, lest you build up a herd that grossly exceeds the land’s carrying capacity, resulting in severe overgrazing, and animals starving to death. Keeping old animals alive for as long as possible means meeting their higher nutritional requirements than what the younger, more “in their prime” animals in the herd need, ’til death do they part.

For sure I thought I had hammered down the myth that it was unnecessary to kill animals for food. Until I remembered one particular question that I wrote out a lengthy answer to on a now-defunct Q&A website called Answers.com, Are cows happy to be killed? Then it all came tumbling back: I really had completely missed some pretty important points.

While this question is indeed rather odd (to some, rather offensive), it raised several important questions including how do animals actually view death; what are prey-predator interactions, and how does this relate to human-cow interactions in terms of humane handling and slaughter; what makes humane slaughter “humane.” To me at least, it readily questioned the vegan mantra that, “all animals want to live, none want to die;” as well as if cows really do see, understand and fear death in the same way we do.

Most importantly, it revealed how and why humane slaughter/euthanasia is no myth, and why killing animals for food is still necessary, rightly justified, and definitely not some form of wrong-doing. I hate to reinvent the wheel, but it serves justice to reiterate much of what’s been said in the Answers.com question above here.

Well, It’s No Wonder…

Let’s face it, vegans have it right in that they are so vehemently opposed to industrial animal agriculture. It has become one of the worst ways to raise animals not because it’s unnatural, like agriculture, in the construct of its very nature, isn’t natural at all, but rather because animals are not free to express their God-given qualities and characteristics that make a pig a pig, a cow a cow, and a chicken a chicken. They are inherently and deliberately prohibited from doing all the digging, grazing, and scratching to their heart’s desire, and instead are turned into grain-eating, flesh/egg/milk-pumping machines: mere commodities. That just ain’t right.

I know that the vegans really like to throw out how many billions of animals are killed every year; somewhere in the 60 billion annual estimates. Most of these are chickens, upwards of 90 percent. I have heard some claims that an industrial slaughter plant has the capacity of slaughtering 140 chickens per minute, or 400 cattle per hour. That’s a lot of death in a short period of time.

Now here’s the most frightening part: I have heard that employee turnover rates at these plants average about 100% per year. That means that every single year there are always untrained employees that come into these large plants that are expected to process so many animals, so many animal carcasses per minute or per hour, and the company responsible for running these industrial plants must take the time to train these employees on proper slaughter procedures and handling of equipment and tools to do the job properly. But is the proper training being done, and are these employees as skilled as they should be to perform the slaughter process as need be? My money’s on a big, fat, NO. They’re most likely not nearly as skilled as someone who’s been trained to slaughter an animal using only a very sharp knife and takes the time to do a proper job.

White Oak Pastures, which has an on-site slaughter facility, harvests somewhere around 20 cattle per day, and maybe 40 chickens per hour. I could be off on those numbers, but that indicates to me that highly skilled butcher-men (and butcher-women) are involved to make sure that the animals are handled by true professional staff that actually knew what they were doing and give a schitzen about the animals, unlike those hundreds of employees in those giant industrial slaughter factories.

It’s no damn wonder vegans think humane slaughter is such a big myth…

The True Moral Responsibilities and Obligations To Animals

Many a non-farming folk ask: “How can farmers care about their animals, and yet send them to slaughter?”

The answer to that is fairly easy, but difficult for most people to really understand—most people, as in the “normal” Average Joe/Jane whose parents and grandparents have lived in suburbia or somewhere totally urban and have virtually no agricultural knowledge under their belt. I’ve been told though, that I have quite a knack for explaining things in ways that the average non-farm folk can understand. So, here it goes.

The biggest take-away point that most of you can come away with is this: We (including farmers) have the moral obligation and responsibility of not keeping our animals alive no matter what.

Wait, what??

That’s right. We have the moral obligation and responsibility of giving the animals in our care the best life possible. But that doesn’t make it mandatory that we must also keep them alive for as long as possible, no matter what the situation may be, no matter how much pain and suffering they’re in, no matter what emotional connection we have with that animal and the heartache we’d experience with letting it go.

See? I told you talking about death is tough.

Just as farmers have the moral responsibility of giving the best life possible to the animals in their care, don’t those farmers also bear the moral responsibility and obligation to give their animals the best death possible when the right time comes?

Yes, they do.

I purposely brought up the moral argument because pretty well all vegans try to take the moral high ground in espousing that it’s morally reprehensible to kill an animal for any reason whatsoever. As one of them told me recently,

“…cows like all animals [sic] are sentient beings with rights and desires of Their Own [sic] like the desire to live free and not be pinned up [sic] their entire lives until someone shoots them in the head or slits their throat.”

Remember what I said about how the only way most people can relate to animals is through human thoughts and emotions? To put it another way, they imagine themselves as the animal that is going through all the rigours of life on a farm.

To that extent, they abhor the killing of animals so much that they equate it to homicide. To them, slaughtering an animal is the same as murdering a human in cold blood. So, they deliberately use the word “murder” to establish their position of abhorrence, and certainly to effectively create an immediate and hard-hitting emotional response in those they oppose (or are trying to convert). “Meat is murder,” they proclaim; “You murder animals for your palette pleasure,” is another popularly infamous guilt-inducing mantra. Believe me, there’s always more where those came from.

I can’t remind you enough about the fact that the position these vegans come from is only via anthropomorphism. That’s the best way to explain it, because I’m no psychologist and don’t know all the other fancy terms that psychologists use to explain the mental gymnastics that these anti-death missionaries practice on a regular basis.

Listen, there is no doubt that deliberate and malicious human-on-human killing is a horrible and unforgivable crime. But applying that kind of wrongdoing to animals? I question that it is as morally reprehensible to kill an animal just as it is to deliberately kill another human. There are exceptions of course where killing an animal is not warranted nor encouraged, such as and especially killing for sport or pleasure and letting the animal’s body go to waste. That, in my book, is a ginormous No-No.

When it comes down to killing animals for food (when the time is right to do so), or euthanizing a sick or seriously injured animal, though, how someone finds that offensive is appalling and mind-boggling to me.

The job of every farmer is to give their animals the best care possible. That’s an obligation and a hefty responsibility that every single farmer carries on his or her shoulders. (There are certain types of operations that could certainly do far better than they claim they do but getting into that discussion would take this post off track entirely.) That means giving those animals good quality feed and water, the kind of health care service that would make most people jealous, and facilities to keep them safe from predators and other things they could get into trouble with.

When it’s time to “harvest” them, practices have been developed over many years of research and study, particularly by those of the likes of Temple Grandin, in that the method of slaughter is quick and virtually painless; not slow, extremely painful, and drawn out as the kind of unfounded rumours I’ve heard quite a number of vegan keyboard warriors try to spread to anyone who will listen/read. More on that a little later.

I should think then, that if animals in our care deserve the best life possible, so they should also deserve the best death possible. Am I right?

Anthropomorphism and the Fear of Death

I won’t tire of repeating the fact that most people view animals from a very humanized point of view. There’s a sciencey-term for that, called “anthropomorphism.” It’s an innate tendency of the human psyche to, as per the definition, “attribute human characteristics or behaviour to a god, animal, or object.” In other words, it’s interpreting animal behaviour in terms of human behaviour so as to rationalize and reason why an animal acts the way it does. Or, it’s a bad instinctual habit of seeing an animal as a furry, feathery, or scaly version of a human so as to best relate to that animal.

Anthropomorphism isn’t totally bad, as it’s what has helped us gain the kind of companion animals we have, like dogs, cats, horses, or guinea pigs… But in the context of this post, I use the term to illustrate how extreme things get taken in the arguments against killing animals for food.

You’ve already read one of the most popular mantras used in social media against food animal slaughter: “There’s nothing ethical or humane about killing some[one/thing] that doesn’t want to die.”

That last underlined part really highlights the use of anthropomorphism to reason out why vegans vehemently believe that killing animals is immoral and wrong. But I’ve been curious as to why such reasoning is even used, and on such a consistent basis.

While writing this I was really trying hard to find some hard, solid reasoning behind these beliefs, but was consistently disappointed by the numerous vegan websites I visited. None of them, and I do mean none of them, provided a good, solid, water-proof reason for why they believe killing animals for food is wrong. All of them provided such shallow justifications it’s rather pathetic; almost laughable.

Really, the only superficial reasoning they had was via the comparison of the definitions of “humane” versus “slaughter,” and used those terms to point out that humane slaughter is an oxymoron of sorts. The definition of humane is “having or showing compassion or benevolence;” and slaughter is “to kill (animals) for food.” Neither of these definitions appears to jive, at least to some folks. This brings up one little problem though: Do any of these vegan sites know what an oxymoron is, and how it’s actually used in literature?

An oxymoron, according to Wikipedia, is a “rhetorical device that uses an ostensible self-contradiction to illustrate a rhetorical point or to reveal a paradox;” basically it’s just a figure of speech in which contradictory terms appear in conjunction with each other so as to stir up a little drama for the reader. So, in a way humane slaughter is an oxymoron, but not in the way that vegans have most people thinking. I suspect that the person who came up with the term “humane slaughter” was absolutely brilliant in how they came up with such a term that was either deliberately meant to get animal rights activists all up in a tizzy or to purposely illustrate a paradox between what is humane, and what is slaughter.

Thus maybe humane slaughter is far more of a paradox than an oxymoron? Or, perhaps both? Now there’s a thought to get your literary and critical-thinking wheels turning.

Really though, I figured that the vegan activists would come up with something better than just term definition comparisons. Either I guess I gave them too much credit or set my expectations of them a bit too high. Oh well.

The only place where I actually found some exceptional reasoning was from Rhys Southan’s blog, Let Them Eat Meat. Rhys provides a very deep and lengthy philosophical view of killing and eating animals, among other things, yet they’re points that make a whole lot of sense, at least to me. Most of the vegans think he’s insane, which I find very amusing. Before I offer up a quote from his blog, I have some thoughts that need saying.

Let’s look back to the definitions of both humane and slaughter—in sort of playing the vegan’s game. We know that “humane” certainly means to be kind, compassionate, benevolent, nice, overall just a good thing or person to be. That’s quite obvious. “Be kind to animals,” as the vegan-gelicals always like to remind us. But then, we get to the term slaughter, which literally means to kill. Now, here is where the vegans are convinced that “humane slaughter” is an oxymoron: In their minds, to kill is a correlation-implies-causation argument because killing is pretty much always associated with malice and malevolence. Homicide (in the first and second-degree murder) and manslaughter are typically a result of overwhelmingly irrational anger and hatred for another human being, leading to extreme behaviours that are the worst form of criminal acts that can ever be conceived.

There’s just one problem though: Killing isn’t always associated with malevolent actions. Killing can also be a result of self-defence against someone with malevolent intentions, as well as a product of war. Also, in nature, I highly doubt a pack of wolves feels such malice that they would bring down a moose or bison. They kill for food and to be able to simply exist. There’s no other justification for a predator’s actions. Killing for the wolves (or the lions or owls or hawks or weasels or coyotes…) is with some form of intent, but certainly not malice. It’s not with benevolence either, though. In their intentions to kill for food, they are neither being intentionally mean and cruel nor are they being compassionate and kind. There is no way of describing it. If there is, leave a comment below.

In the construct of humans killing animals for food, then, there really is no malice involved in such an act as putting a bullet or cap-bolt into an animal’s brain followed by immediately slitting its throat. There is certainly intent, as there must be when the process of slaughter must be done as quickly and efficiently as possible. But if there was any malice involved, there would be no reason to ensure that the right-calibre and type of bullet is placed at the right spot in the forehead at the right angle, nor would there be any reason to ensure the blade of the knife that pierces through the jugular vein and carotid artery is so sharp that a man can easily shave with it. Instead, if an animal should be killed with malice it would be done in a way that the animal is going to be clearly showing signs of pure agony and distress as its life slowly ebbs away to nothingness. That’s called torture, in case you didn’t know.

Correlation, then, does not mean causation. Just because human-on-human killing is often associated or, sorry, correlated with malice, does not mean that malice is always a cause of the killing. This is a rather pointedly pathetic form of argument that renders itself illegitimate.

When I try to—and fail—communicate with a vegan about how the killing of animals for food isn’t a form of malice, therefore, making it indeed a humane act when done properly, I get the snarky response of how such acts should be shared amongst those who are known-serial killers. Well I’m sorry, but most serial killers don’t kill their victims in such a way that they’ve no idea what hit them; most kill in the cruellest and vilest means they can accomplish, torturing their victims first before ending their lives and disposing of the evidence. Serial killers enjoy it so much that they’re happy to do it again; it gives them a buzz like nothing else. So, a person has to be really stupid to have convinced themselves that animals raised for food are killed in the same manner. No: correlation does not imply causation.

See, that’s the dangerous part of anthropomorphism: these people who are so far removed from the natural world and from the farm think that animals are just as afraid of death as we humans are, and are thus afraid that if they die they will have never had the chance to live the lives they wanted to live or do the things they’ve always wanted to do… but that’s not how it works for animals! For them, it’s basically going from existence to non-existence, just as they had been non-existent prior to conception, let alone the few months before being born. I have to quote Rhys from his blog, “Killing For a Better World,” as he can explain it better than me:

…yeah, animals are sentient and want to live… while they are alive. But once the bolt enters their brain, their consciousness flicks off like a switch, and they are no different from a plucked flower: non-sentient and without desire. It’s not like killing animals traps them in some horrible limbo where they still have interests but can’t fulfill them. Killing someone removes their identity, their thoughts and their interests simultaneously. The cow used to be sentient and the flower never was, but that was then and this is now: death nulls and voids that distinction. Animals that we kill do not experience nostalgia for the life they no longer have, nor regrets for the things they never got to do. For them, it’s as if they were never born. The only difference between the death of a cow and the death of a flower, then, is what it takes to kill them, the visceral nature of their deaths, the composition of their corpses and how the survivors react. And if the dead animals’ farmyard pals aren’t too broken up about it, where’s the loss?

If death were such a terrible thing to the one who dies, you’d have to be a monster to intentionally have human children. Don’t you realize they’ll become attached to life and yet will die, just like the animals we raise for food? Worse even, since humans are aware of this death and fear it from childhood on, and odds are pretty good that they’ll die of a painful disease that gratuitously draws out the final blow. Breeding non-human animals into existence and killing them swiftly is chivalrous in comparison, since the animals probably d

on’t stress much about the future prospect of death, and then (in a well-designed and competently operated slaughterhouse, at least) are gone before they realize what’s happening.Vegans are fine with non-existence before an animal comes into being. In fact, many vegans prefer us not to breed animals into existence at all. And yet, they’re against hastening animals’ return to non-existence once they’re born, even though pre-birth non-existence and post-birth non-existence are identical as far as the non-existent entity is (non-)concerned. It’s not like post-birth non-existence, which we all get to eventually, is any better if we die later rather than sooner. Life is a vacation that the non-existent don’t remember; to the dead, it doesn’t matter how good or how long their life was. Kill a cow at age one or let it live until 22 and the ultimate outcome is the same: the non-being of that particular consciousness. So all that matters is how the killing affects the living. Does it leave the world better or worse off?

Which is why meat eaters often see meat as a positive for humans and a neutral for the animals we raise for food. If the animals have decent lives, there’s not much for them to complain about while they exist. And once they’re dead, they are back to nonexistence, where they started, no better or worse than if they’d never been born. We’ll eventually die too, but in the meantime, we benefit from having animal corpses to eat.

I am convinced that the whole meaning behind that phrase, “animals… don’t want to die…” is just those projecting their own fears of death onto animals. We, humans, know damn well that we’re scared to die. We don’t want to die because of that fear that we won’t ever get to have all our wants and wishes fulfilled, that bucket list completed before the Good Lord calls us home. So naturally, we’re going to be assuming the exact same thing for animals.

It’s just that animals, though they may indeed be sentient, sure as hell aren’t sapient.

I for one am guilty as charged for talking to animals like they’re some four-legged furry and super cute human. It’s so hard not to. They may not understand the words I’m saying, but I do hope that my verbal communication makes up and helps with the body communication I wish to project to that wonderful beasty. But that’s just communication. When it comes to the whole conjecture about death and dying and then slaughtering animals, it’s a different story. In the end, a cow is a cow, genetically, biologically, physiologically, and psychologically, just as a pig is a pig, a chicken is a chicken, and so on.

I know, I know, that’s a cold and callous thing to say for someone like me. But the reality of it all is that animals don’t have the same concept of death that we do. For them, life is good to have while they’re still alive. They live in the now and do so far better than any of us humans can attest to doing, even me, thus aren’t likely to think about what death is and what happens after they die.

If you’ve ever seen some of the studies done by Temple Grandin and others in the use of calm handling techniques of animals prior to slaughter, you then see how animals that are handled well are very calm and quiet right up to the moment it’s time for them to go. They’re not throwing themselves wildly about, trying to jump the chute or the fence, or crashing into things. No, they’re standing quietly, moving when they are gently prompted, sniffing at things and looking around. Then all of a sudden; lights out.

The only time animals are showing signs of fear and panic is one or both of two very obvious things:

- They smell the pheromones of the animal[s] that came before them that were given off during their panic and fear. A pig nor a cow will question why they smell such pheromones; instead, they react accordingly and start getting scared and panicked themselves.

- They are being handled roughly. Yelling and screaming, beating with paddles or sorting sticks, getting kicked, etc., are enough to push an animal to react out of fear and panic.

Fear of getting caught and trapped is another biggie. Prey animals like deer, moose, bison, run away from predators because they don’t want to get caught. They know from witnessing others of their tribe, herd, group, whatever you want to call it, that terrible things happen when they get caught by a predator, and so they do everything they can to avoid it and live another day. They don’t know that they’re going to die when they get caught, they just know that getting chased and caught is bad and must be avoided at all cost.

Let’s look at it another way. Animals are smart in that they learn to associate certain things with good or bad experiences. If they have had a bad experience that was painful and stressful, they associate that particular thing, whether it’s the squeeze chute or a person with a certain pair of overalls, with that bad experience and do their best to avoid or fight against the force that’s making them having to face that thing again. The opposite is true when they’ve had a good, pleasurable experience; when they see someone come walking out to them, they just know they’re going to get something good today, and will follow that person or hang out with them until they either get bored or get that food (or a good scratch) reward they’ve sought.

Animals get particularly stressed when they’re put into a different environment than one they’re familiar with, like the commercial slaughter plant. Most don’t like it when they have to experience something entirely different today apart from what they’re used to; some get so stressed out that they panic. To those who don’t know animal psychology surmise that that animal somehow “knows” it’s about to die. But in reality, that animal is just panicked by the new and unfamiliar sights, smells, sounds, and feelings, and really wants to go back to whence it came. That’s all. It’s a marked difference from those animals that are slaughtered on-farm.

Those animals that are killed and slaughtered on-farm are done in an environment that is totally familiar with them, and where they are most at ease, right up to when the bullet decimates the brain. They aren’t scared of their surroundings because they’re at home. And they’re certainly not scared when that gun is pointed at their head. Somehow they know they’re safe, even when it’s time for them to go.

I’m of the mind to say that they don’t fear death in the same manner that we do, and don’t know that they’re going to die in the same encapsulated fear that we bear. Instead, I believe that they somehow know that they must “go onwards”, and cease to exist so that their now-vacant, soulless bodies can go towards feeding others. It’s difficult to describe; but it’s some kind of ancient, ancient construct that predates agriculture by billions of years in that things have been feeding on other things in order for everything to even exist, survive, evolve, adapt, and forward their generations onwards and support others in their part of the ecosystem.

Even though agriculture isn’t natural, it has taken animals that are predominantly prey species—even pigs—to be domesticated over thousands of years to be a continuous, sustainable, and much more reliable supply of food for us humans over and above the risks associated with living as hunter-gatherers.

But even with all that, vegans are still adamant that no animal wants to die. Why then, is their argument, the very construct of anthropomorphism, so bloody dangerous not only to us but more so to the animals themselves? I think it’s time I move into that aspect of this discussion.

The Cruelty Behind “Letting Animals Live Out Their Own Lives”…

A quote I found from the Veganuary site that hits on a couple of the points I wish to discuss, like this appeal-to-nature fallacy gem:

…as each of us chooses not to buy animal products, fewer animals will be bred, reared and slaughtered in the future. This is how the supply-and-demand market works. If people don’t buy a product, it will stop being produced. So, if the whole world did eventually go vegan, no more animals would be bred, and farmers would diversify into producing beans, broccoli and beetroot. Since producing vegetables is more labour-intensive than farming animals, there would be more jobs in farming.

Some people worry that individual species of farmed animal would become extinct if people stopped eating them, and for many farmed species this would most definitely be a good thing. Farmed breeds are not natural in that they do not occur in the wild. They were specifically bred by people to have certain physical traits, such as large muscles or high milk yields, but these money-making traits also cause a lot of suffering. Commercial breeds of turkeys and broiler chickens, for example, are bred to put on a lot of weight as quickly as possible and as a result their joints are painful, their hearts are weak and they are prone to bone breakages. It is right that these poor creatures are not bred to be this way. But that doesn’t mean that all poultry breeds – or any other farmed animal species – will completely die out. (Just think of the thousands of species that we do not eat and who survive.) They would need the right habitat, of course, but that would be easier to provide for them as we would need a lot less land for farming.

And this is one of my favourite rebuttals from Southan’s blog

Vegans are fine with non-existence before an animal comes into being. In fact, many vegans prefer us not to breed animals into existence at all. And yet, they’re against hastening animals’ return to non-existence once they’re born, even though pre-birth non-existence and post-birth non-existence are identical as far as the non-existent entity is (non-)concerned. It’s not like post-birth non-existence, which we all get to eventually, is any better if we die later rather than sooner. Life is a vacation that the non-existent don’t remember; to the dead, it doesn’t matter how good or how long their life was.

This is just my own perspective and opinion, but I really do think that those people who are so against the use of animals for food live in some kind of utopian fantasy land. I don’t think I’m alone in that thought…

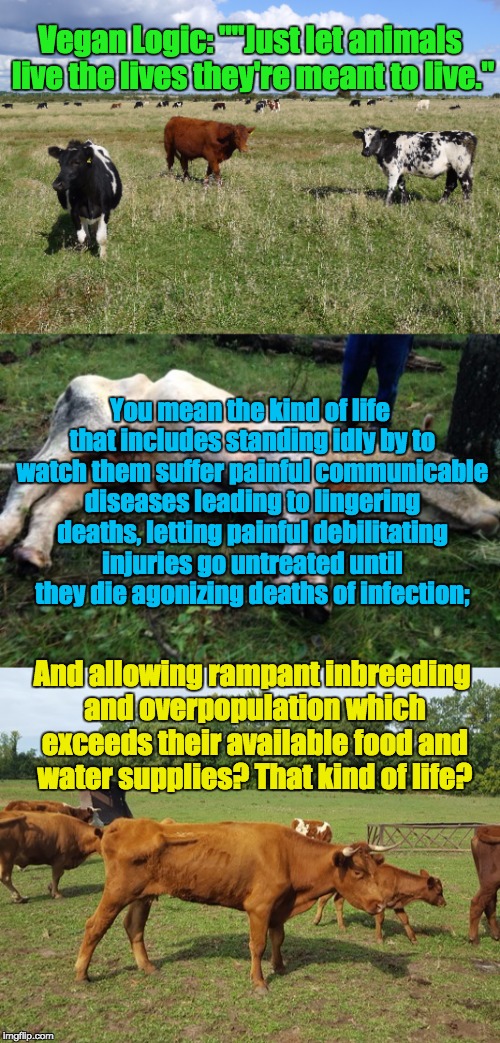

A couple of things come to mind when I consider the mantra that, “it’s best to just let the animals live out the lives that they’re meant to live.” The first two are pretty much as the meme points out:

- Animals much more subject to prolonged and painful deaths by way of illnesses and injuries that are incurable;

- Lack of population control leading to overpopulation and suffering by way of starvation and malnutrition. On the other hand, too heavy of population control eventually leads to extinction.

A third point that comes to mind is the extensive care that must go into animals of old age if such proponents believe that “all animals want to live,” and particularly, “every animal must live their lives, but none should die for others.” This third point actually rounds right back to the first one above.

Let’s look at the first point now as that’s, at least to me, the most important one to talk about in this context.

While it’s nice to think that any animal, especially farm animals—if they were “rescued” from the plight of the industrial agricultural complex and thus the threat of being killed for other people’s “palate pleasure”—that they are now going to live a wonderful life where they won’t ever die such a horrible death as in the huge industrial slaughter plant, it’s not exactly the reality per se. Now, I’m just talking about these “rescued” farm animals that are now somehow “safe” on the numerous animal sanctuaries and rescues, not the ones that vegans have tried to liberate from their “prisons.” I’ll talk more about that in a little bit.

For me, the more I dig into these animal sanctuaries, the more ugliness I discover. While the people who run these glorified petting zoos have good intentions, I find most of them have no idea what they’re doing when caring for these animals. My biggest question of all, and one that I find gets swept under the rug the most, is what happens when they get an animal that is suffering from an illness or even incurable disease? What sort of efforts do they go to make sure that the animal is comfortable and most importantly, not forced to go through any prolonged suffering just because of some religious dogma these people are forced to follow?

My sneaking suspicion is that these sanctuaries–because they are completely against the very concept of taking the responsibility of determining when an animal should die–make sure that they don’t ever euthanize an animal. Instead, they seem to be all about letting it die a so-called “natural death” on its own. This may sound unsubstantiated to some, but my spidey senses sure get tingling when I read the “in memorium” of animals that have died in these places on these sanctuaries’ websites.

One such case that I talked about quite some time ago involved Dudley the Hereford steer that was “rescued” by the Gentle Barn. You can read more on that in the link just provided here. This poor animal had to have his hind hoof removed because of the plastic baler twine that got ensnared on it, cutting off blood supply for so long that the hoof started to slough off. When rescued, the folks at the Gentle Barn had the hoof removed and a prosthetic leg put on. The videos of Dudley via The Dodo showed a very ephemeral image of a happy, bouncing, and playful animal that just got his life back. But truthfully, that joy was quite brief. It wasn’t long before that steer was showing signs of distress, of excruciating pain, and that he was clearly suffering. Unfortunately for poor Dudley, the sanctuary was so barn-blind to his plight that they kept paying to do all these unnecessary surgeries on him (not to mention making him the sanctuary’s mascot and acting like he’s in perfect health to all their supporters), making every effort they possibly could to make sure he lived. This, even though he was screaming at them, in the only way he could, that he was in so much pain that life wasn’t as joyful for him as was displayed in that video. In the end, it was the veterinarians (who performed all the surgeries) who took the responsibility to make the ultimate decision that an end to all that madness had to happen. They put Dudley in a far better place than the Gentle Barn could have ever been capable of; they did the very thing that should’ve happened when that poor bugger was found with that baler twine wrapped around his hoof. But you know what really pissed me off about this whole Dudley thing? The Gentle Barn spun the story into one big fat lie. They claimed Dudley died of something that he honestly didn’t. To put it bluntly, Dudley died by sheer and utter ignorance of those he blindly entrusted to care for him, not of a stomach that got ripped apart.

Dudley is only one story. What of the hundreds or thousands of deaths that have not yet been told?

See, here lies the very challenge to those who are so vehemently against animal slaughter: Why is it seen as being far crueller to kill an animal with a well-placed bullet or cap-bolt and via exsanguination (slitting of the throat) with a very sharp knife, than it is to allow an animal to die a slow and excruciatingly painful death of an incurable illness or disease?

This is where I begin to really push buttons. Those who go about acting like they give a shit about the animals, and go on and on about all the atrocious conditions they’re forced to live in, how cows are “forcibly impregnated” and calves are “ripped away from their mothers,” seem suddenly indifferent to an animal that is slowly dying of an illness or injury and experiencing the greatest kind of pain any kind of sentient creature could be forced to go through. To me, that screams that these people don’t give a flying f*ck about the animals.

Where’s the compassion and kindness to an animal that can’t be saved, to one whose continuation of life is only guaranteed by an endless supply of intense chronic pain and suffering?

It’s not the vegans who are the compassionate ones in this case. There’s no compassion nor kindness involved with sitting by and watching an animal slowly die. Where there is compassion, however, is where an individual will grimly, yet determinedly, take on the full responsibility of putting an animal out of its misery with a well-placed bullet. Do you know what kind of individual that is? A farmer, that’s who.

A farmer will put every effort he can to make sure that a sick animal gets the treatment it deserves and does the work to put it right back to health again. But if nothing is working, and the diagnosis by the veterinarian says that the cow won’t recover to her old self again, then there’s not much else to be done except to send her to get converted to meat, or to euthanize on the spot.

Hey, I don’t see any vegans or animal sanctuaries offering up any other better solutions than what they’ve already tried and failed to do.

Okay, now what about the perfectly healthy animals that are sent to slaughter or killed on-farm for food? They’re not suffering any painful maladies, they’re quite happy living their lives. Why must they be killed?

There are two primary reasons. One which I’ve talked about previously is in regard to feed supply being a finite resource. There’s only so much feed that can go around, and only so much pasture that is available for only so many animals. Second, it can be costly to keep having to feed animals that are not giving back to the farm in some manner. We tend to call these animals “free-loaders,” as they cost a lot to keep while giving nothing in return year after year. A farm is a business, not a hobby, and should be treated as such. Farms don’t rely on suckering in gullible, ignorant people who have their hearts on their sleeves for donations. They have to sell a product to help the farm to continue to run for years to come. Animals are a part of that business, just as the farmer is.

Every single animal sanctuary should know how much feed it takes per year to keep a bunch of free-loaders alive year after year. Seriously.

Let’s turn the tide towards animal liberation. In the context of “letting animals live their lives as they see fit,” the vegan liberationist utopian belief is that any animal that is released from their imprisonment will somehow go off on their

own and find their nice little families and live a happy long and healthy life in their own home with all the wants they desire. What a load of hogwash; both highly amusing yet maddeningly asinine at the same time.

I believe this unfounded belief is based on the premise that every animal that is encapsulated in agriculture has somehow been forcefully brought in from the wild and made to live a life within the confines of a fence, barn, or cage. That sentiment couldn’t be farther from the truth.

All animals that are farmed, be they cattle, sheep, goats, pigs, chickens, ducks, turkeys, llamas, horses or alpacas, have been domesticated over thousands of years to live in close coexistence with humans, to the point where they have learned to lean on humans for food, water, shelter, and protection from other predators. Over thousands of generations of animals, this reliance has become second nature, and with the help of humans, is passed on from one offspring to another.

These animals have only known safety from the confines of the barn they’ve lived in all their lives, or the fenced enclosure that they’re confined to. I doubt that they question what’s beyond that door or on the other side of the fence. Perhaps they do as a brief passing thought, we’ll never know. More often than not, it’s that space that they prefer to stay.

Animals really like to stay where they feel the safest. They don’t like being where they feel they’re not safe. If they are granted an opportunity to wander, they will wander. But unlike most of us (or at least those of us who have a good grasp of the predator-prey interactions that happen when you let a bunch of chickens, sheep, goats, cows, or ducks loose), they have no idea of the dangers that lie beyond should they continue to wander aimlessly about.

Except, that’s not what some animal liberationists believe. They think that it’s going to be so much better for the animals if they cut the fences and let them loose. There are many cases involved with such activities that point how that turned out to be far worse for the animals, or a complete failure for the activists.

One such case occurred over a year ago on Taranak Farm in Australia. All of the free-ranging pastured layer hens were released in the middle of the night by some animal rights activists. All of those chickens were killed by dogs, foxes, hawks, or just disappeared never to be seen again. None of those chickens had any knowledge of how nor where to run for cover to escape these predators, NONE. The only safety they actually knew was in the confines of that fence that those stupid activists cut open. That fence was there for those chickens’ own protection, not to imprison them in some kind of “concentration camp” nonsense.

Another case was when another dumbass activist tried to free a herd of dairy cows, only to have them get all milling about and wanting to go back to the muddy corral they felt perfectly fine to be in. At least the cows were smart enough to stay put and not go wandering out where they could become a serious hazard on the road…

There have been other cases where animals were deliberately killed by activists from just plugging off the ventilation or putting a match to a barn full of animals.

Is any of this really a show of compassion? I think not.

Going back to the “liberated” animals versus predators, the question becomes, did the animals die better deaths by predation than if they were to be killed for food by humans eventually? The very obvious answer to that is no. Predators usually don’t make sure their prey is dead before they start eating on them unless it’s a big cat who prefers to suffocate their prey first before letting the feasting begin. Most of the time, the killing done by the predator is so traumatic and violent that it shocks an animal’s system to shut-down-shocker mode. It can still be alive as it’s being eaten. Of course, the predator doesn’t realize it’s being “mean” to its prey, it’s just doing what it’s naturally designed and instinctively learned (now there’s an oxymoron for you) to do.

Animals that are “liberated” only to have to die horrific deaths isn’t an act of kindness, caring, nor compassion by any means. Quite the opposite. We humans at least have the brains enough to come up with solutions to make sure the deaths delivered to prey animals are so quick that they didn’t know what hit them, and they die very quickly. Why else were guns, knives, and other weapons of the trade invented? Think about it.

So now, what if we really did let these animals “live their lives as they see fit” and had no means of controlling them. What then? Well, very basic biology states that when an intact male can get together with a receptive female, babies can happen. Depending on the species, and if conditions are right for their survival, lots of them can happen. Just look at the feral pig situation down in the southern half of the United States.

Some may scoff at the notion that overpopulation can happen if a bunch of farm animals were let loose. I can safely say that those scoffers need to pay better attention in basic biology class. Animals don’t regulate themselves. They don’t understand the whole safe sex or use of contraceptives or even abstinence thing that we humans do; If there’s a female in heat, and a male’s ready to breed her, that breeding will happen.

I’ll stop here because I already talked about overpopulation in another blog post I’ll link HERE. No sense in repeating myself…

To bring this around to the third point, these animals aren’t meant to live forever. They get old, they need good care until they die of this “natural death” that vegans always mention.

Here’s the problem with getting old: Old animals get aches and pains and chronic illnesses just like old people do. These old animals need the extra care to continue to live, and that extra care can be quite costly, and I don’t just mean the food bills: there are the veterinarian bills to consider too.

I hate to sound so callous but is it really worth it to spend that extra money on an old cow or hen that’s near the end of her life, just so you have the fleeting satisfaction of having her live a little longer? Is it really in the best interest of that animal to keep it alive, or is it more for your own selfish desire?

Personally, I think it’s rather selfish and a disgrace to force an animal to live for as long as possible, even when that animal is suffering some chronic illness (or injury as in the story of poor Dudley above), just because a person is too scared of death or even too full of pride to take the responsibility of making the ultimate decision of letting that animal go. Besides, an animal dying of old age is exceedingly rare in nature. If we want to start talking about dying of natural deaths, let’s talk about the billions of animals that are killed by predators every year. That’s dying a natural death.

I also hear a lot of whining about how many farm animals are killed when they’re young; that they’re not “allowed to live to their full natural lifespan.” I find that amusing both because, as I mentioned above, it’s very rare for a wild animal to live to old age, and there are many young animals that don’t make it past the first month or first year—some even the first day—after birth. For example, the average survival rate for a fawn to six months old is around 1 in 3 or over 30%. Most fawns are preyed on. This is no different (with a little more variable survival rates, from 1 in 5 to 1 in 2) with other young wild animals, no matter if they’re goslings, bear cubs, fox pups, seal cubs, caterpillars, mosquito nymphs, ducklings, elk calves, etc… All of these young animals that don’t survive to become adults will certainly die of natural causes. Besides, it’s a rather dumb appeal-to-nature fallacy to even bother bringing up the talking point about such short lifespans of domesticated food animals; mainly because all aspects of farming are not natural. It’s always been a construct of human thought and endeavour.

I’ve got news for you vegans: Every single food item that you eat isn’t natural; it isn’t naturally found in the wild. Every single plant species that is grown to fill your forever-hungry bellies is man-made. From soybeans to corn, from rice to wheat to quinoa to lettuce, broccoli, kale, carrots, cauliflower, beets, mangos, apples, strawberries, dates, dry beans, peas, lentils, chickpeas, bananas, pineapples, avocados, onions, potatoes, squash, tomatoes, and so on. So, stop with the stupid “but it’s not natural!” arguments because you’re making yourselves look like a bunch of babbling fools.

There is one more thing I really need to talk about before I finally let this post go, and give you a bit of a relief from reading this lengthy article. It has much to do with the deaths of animals in plant agricultural production.

The Least Harm Fallacy of Veganism: When Suffering-Reduction and Intent Arguments Keel Sideways

Without further ado, I give you two pieces to read. One is the blog post that was written on the Ethical Omnivore Movement’s website you can read HERE, and the second is a piece written by Rhys Southan on the Killing for a Better World post I’ve quoted before above, the latter which I provide a nice long quote:

The suffering reduction argument says that veganism causes less harm than non-veganism because it kills fewer animals and causes less pain, and so is ethically preferable. The intent argument says that there’s a major ethical difference between killing animals unintentionally – even if we know that a certain action will cause their deaths – and the intentional killing of animals for their bodies.

In response to the suffering reduction parry, meat eaters can try to show that there are ways for meat eating to cause less suffering than veganism. For instance, you can cause less suffering by replacing some vegan agriculture with hunted animals, insects, elevation-raised bivalves, or grass-fed ruminants. Or meat eaters can say that vegans are reducing suffering to an arbitrary level because they aren’t reducing suffering as much as they possibly could (freegans who only eat food that would otherwise go to waste reduce suffering more, as do people who don’t spawn children and who convince others not to have children); how can vegans demand that meat eaters stop compromising on the amount of suffering they’re willing to reduce when vegans compromise on the amount of suffering they’re willing to reduce too?

At this point, vegans are likely to shift the debate from suffering reduction to “intent,” and suggest that it’s worse to kill animals purposely, as meat eaters do, rather than accidentally, as vegans (and meat eaters) do.

One possible meat eater response to the intent claim is that it just doesn’t make sense to apply our intent standard to our killings of non-human animals because the animals we kill are completely unaware of our motives, and even if they were aware, it wouldn’t help them. Intent is a human-centric concept with no practical applications for other animals.

When judging the severity of a crime, humans consider intent for two main reasons: to help determine if they’re going to commit the crime again, and to satisfy our desire for revenge if the action was malicious, and thus especially enraging. We assume that if a criminal intentionally shot someone, they’re more likely to kill again than someone who knocked out an AC window unit by accident. However, our “accidental” killings of animals who get in the way of our crops aren’t due to temporary lapses or clumsiness – they’re routine consequences of something we’re not going to stop doing. These deaths aren’t whoopsies so much as predictable casualties that we’re willing to accept.

The revenge aspect of intent also isn’t relevant to other animals in their dealings with us. Since they will never really know exactly why we’re hurting or killing them, there’s no way for them to treat us differently based on our malice or lack thereof.

Setting motives aside – which non-human animals have no choice but to do – animals aren’t any better off starving to death because we’ve developed their land, or being crushed or chewed up by our farm equipment because we’re harvesting our crops, than they are when we slit their throats.

Another response to the intent argument is that veganism doesn’t avoid killing animals intentionally either. For one thing, pesticides in vegan agriculture intentionally kill animals – that is their job – and rodents, birds, deer and other “pests” are also killed intentionally to protect vegan crops for human consumption. Vegans are against killing animals for meat, but don’t seem to be against killing animals for fake meat.

To this, vegans are likely to say that they advocate some form of agriculture that keeps animals away from crops without killing them. If these vegans consider insects to be sentient animals, then this would mean doing away with pesticides. But even if vegans were okay with eating food that’s sometimes half-devoured by creepy crawlies, there is still a problem here, because no matter what form of agriculture you advocate, by developing land in any way, you can’t help but violate animals’ interest in their homes and also their lives. Dumping sewage, paving roads that fragment habitat, taking water for irrigation or to quench our thirst, chopping down trees for paper or wood, or building a town all constitute direct and intentional destructions of animal homes. This may not be intentional murder, but it is an intentional violation of animal habitat, which is something animals cannot live without. So how does intentionally violating animals’ habitat interests jibe with a philosophy that claims to stick up for all of animals’ vital interests?

The way vegans typically use “intent” is to suggest that if a certain action can theoretically be done without harming animals, then it’s okay to do it it even when it does harm animals. For instance… No matter what, an animal has to suffer and/or die for us to be able to eat its flesh. For vegans, this automatically puts meat in the off-limits realm of bad intent. But if there were no animals in the world other than humans, it wouldn’t harm any animals to chop down a tree. Therefore, chopping down part of a forest is theoretically okay because it need not harm any sentient beings.

However, because there are animals all over the place and they make their homes in and around trees, chopping down trees does kill animals: it either kills them immediately or it kills them slowly by destroying the habitat they rely on to survive. Nevertheless, vegans say we can overlook this. Since chopping down trees is not in itself bad, as a tree is not a sentient being, it’s fine to do this even while knowing that there are sentient beings around the trees who are going to get hurt and die. All we have to do to make this ethical is say that we theoretically don’t require that animals die for us to clear trees away for a road, or to get paper and wood, and we regret that their deaths are an inevitable consequence of our justifiable vegan actions.

The logic here reminds me of that scene in The Simpsons when Bart and Lisa “accidentally” hit each other with their whirring arms and punching fists and blame each other for falling into the line of fire.

It’s also a bit like saying it was okay for the Europeans to take over the Americas because theoretically this wouldn’t have required killing any humans if there weren’t already humans inhabiting it. Sure, the Americas were inhabited, but it was still fine for Europeans to take them over because North and South America weren’t themselves sentient beings who were being harmed. The European invaders would have preferred the continents to have been uninhabited so that they wouldn’t have needed to kill anyone to move there or plunder the natural resources, so their intent was good, even if the process of them moving in necessitated the side-effect of a lot of killing because of the unfortunate fact that Native Americans happened to be in the way.

This isn’t a perfect allegory because much of the killing of Native Americans involved directly murdering them, and when compared to how we treat non-human animals, that’s more like hunting than habitat destruction. But there were policies that took Native Americans off their land and hastened many deaths without always killing them on purpose, like “The Indian Removal Act” and the Trail of Tears, and these do fit with vegan notions of how it’s okay to treat non-human animals.

Since vegans like to challenge meat eaters by asking “what if you did it to humans?”, let’s turn it around on them. If vegans are okay with the destruction of animal habitat as long as we aren’t doing it to purposely kill animals, what if we treated human homes the same way? What if we knocked down human houses without compensation in order to re-develop the land, even if we didn’t know whether there were humans inside or not? The houses aren’t sentient, after all, and it’s not like we want there to be people inside who will die, so is this cool? What about taking over areas of the rainforest that humans live in, and evicting them and essentially killing them?

If vegans object to violating human habitat interests, but not animals’ habitat interests, how are they not hypocritical speciesists?

With All That Said…

In all that has been written here (and linked elsewhere), I believe it can be clearly stated that humane slaughter certainly isn’t as big of a myth as we’re being led to believe. While I didn’t get into how exactly animals, particularly bovines, are slaughtered for food–mainly because that would make this long post too long, and too since it deserves another post in itself–I hope I achieved the capacity to communicate to you the importance of ethics and morals with determining what’s actually right or wrong in how and when an animal must die.

Our moral obligations–in the responsibility for caring for animals–go not just with giving them the best lives possible, but also the best deaths possible when that time must come. Our moral and ethical obligations certainly are not in credence with keeping them alive for as long as possible no matter what. That’s rather selfish, inhumane, unethical, foolish, callous, and completely immoral particularly if we’re far more concerned with the animals’ well-being than our own selfish pride and ego.

While anthropomorphism is certainly a great thing and a fun thing when interacting with animals, taken too far it spells disaster and becomes a form of disrespect, particularly in the context of carrying the hefty responsibility of caring for all creatures great and small, in life and to death. I watched one video from Plant Based News about one lady who was so morbidly horrified at this one farmer who said he had control of which animal lives and which animal dies. This woman obviously had never carried such an enormous responsibility before to even understand the entire context of what that person was actually communicating. I sincerely hope that she finds this blog post and takes the time to read through it carefully and diligently so as to fully understand why it was rather childish to get so emotional over such a matter.

Anthropomorphism is also dangerous in how it can lead to the cruel treatment of animals through the well-meaning intentions of those who wish better lives for them. Things like animal sanctuaries that often get too blinded by their no-kill dogma create greater suffering than what happens on most farms, a sure-fire case of creating what they fear the most. Or, worse still, people who go out to “liberate” animals from their confines in hopes that those animals know enough what to do with their freedom to be able to survive for months or years to come, only to have most of those animals die horrible deaths from predators, starvation, or being turned into roadkill. And what about the fantasy that animals should die natural deaths of old age? Unfortunately, most people don’t seem to realize that dying via a natural death typically happens by predation, and often occurs to young wild animals; it’s very rare for wild animals to live to old age and die of old age like those poor elderly people stuck in a senior’s home or in the long-term care unit of a hospital.

It seems to me that without even getting into the whole how-to of slaughtering animals, I’ve probably been able to show you how ethics and morals apply in, well, justifying the very ancient means of killing animals for food.

Here’s the thing as it stands: Life begets Life. Life is completely incapable of existing without Death. Everything that lives, dies. And everything that lives shall die to feed others. All simple concepts that haven’t changed for the past several billion years, and will never change for many years to come.

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks