(VERY LONG POST. SORRY.)

This meme has been around for a long time. A couple of decades, at least, as I remember seeing it on ancient places like MySpace, Disqus comment sections, Twitter (well before it sold out to become X), and in old Facebook vegan vs. meat-eater debate groups I used to frequent. Even before then, it was a bumper sticker slogan repeated often long before it became a meme.

And guess what? Its (my belief) origins come from a 1971 book (reprinted multiple times, the latest in 2021) called Diet for a Small Planet by Frances Moore Lappe. The quote on page 9 of Book 1, Chapter 1 sounds almost precisely, word for word, what is stated in the meme:

It takes 16 pounds of grain and soybeans to produce just 1 pound of beef in the United States today.

Funny that, eh?

Dr. Vaclav Smil, author and Professor Emeritus of the University of Manitoba, Canada, came later with some feed conversion ratios that seem like an attempt to debunk Lappe’s seemingly unscientific nonsense without directly mentioning it as such.

But Smil doesn’t advocate for veganism, even though he acknowledges that:

Feeding domestic animals is a far more inefficient way of using plant biomass than eating it directly..

–.

Vaclav Smil: On Meat, Fish and Statistics: The Global Food Regime and Animal Consumption of the United States and Japan. Link: https://tinyurl.com/244e954h

Instead, he stays in the middle between understanding that people still need to eat meat and that vegetarianism is viable to a limited extent. Smil’s more balanced view of [animal] agriculture and the human diet tends to rub extremist vegans the wrong way.

Unlike Lappe, Smil acknowledges the major issues surrounding industrialized animal agriculture (CAFOs [confined animal feeding operations] or “factory farms”) and that animal agriculture is still very important to human civilization. He has also acknowledged better ways to raise animals for food, like regenerative (or sustainable) agricultural practices.

Vegans don’t like that, though. To them, it’s still unjust cruelty because “these innocent sentient beings are needlessly murdered for your tastebuds. It doesn’t matter if they’re raised “regeneratively;” they still end up in the same horrific place and face the same horrific, unnecessary end when they don’t want to die.“

Lappe, on the other hand, points out the critical issues of “factory farms” and that the only solution is to stop eating meat and dairy products altogether. Her distinct presumptions against animal agriculture make her a favourite among the vegan community. This explains why they prefer Lappe as a “legitimate” source over Smil and continuously repeat this statistic like it’s an inarguable fact set in stone.

Origins of the Statistic and Its Respective Meme

Where did the original meme come from? There are a few possibilities. One is most likely from a Facebook post made by a vegan advocacy page that I won’t bring attention to. The second is from a vegan website you’ve never heard of before, and I also don’t want to bring attention to here (though, if you’re curious, the source is clearly stated in the meme below: in the site, look under “Human Hunger”).

This meme intends to attack animal agriculture and use famine and poverty as a victim and causation of it. I won’t discuss human starvation or famine here because it would take up too much time and space to do so. Instead, I want to focus on the 16:1 statistic and a few idiotic claims surrounding them.

I also want to break down how Lappe got the 16:1 statistic and then prove whether or not it’s based on reality.

But first, let’s hear from Vaclav Smil and what he has to say about the feed conversion ratios of beef cattle.

Dr. Smil’s Take on Feed Conversion Ratios of Beef Cattle

In Smil’s 2013 book Should We Eat Meat? Evolution and Consequences of Modern Carnivory he talks a bit about the feed conversion ratios of beef cattle.

Now, sadly, the copyright permissions (or lack thereof) information in the book prohibits me from sharing much of what he wrote. However, I believe I can get away with posting a few key quotes that may interest you. I can explain the rest in plain language (the book makes for some dry, heavy reading, almost like reading a scientific journal paper) to save you the trouble of finding the book and interpreting it all yourself. (I mean, if you want to find it at your local library or buy it off Amazon or wherever to read it, I won’t stop you.)

… the recent feed conversion efficiencies [show] an average ratio of about 12.5 kg of feed/kg of live weight of cattle and calves [in terms of] the complete cost of beef production… in equivalent feed value of corn.

This is a very deep approach compared to what I’ve attempted below by copying how Lappe did it. This value is based on the need to meet lifelong maintenance metabolism needs of the body, plus the feeding needs of the sire and dam and these under all types of production systems.

Smil states that it’s useful for aggregate accounting, basically by knowing how much feed is consumed. Still, he cautions that it confuses the kind of feed conversion ratios developed for non-ruminants (like pigs and poultry) because ruminants’ nutritional needs and digestive physiology are quite different.

Beef cattle (funnily enough, it’s the same as dairy cattle) are not required to be kept on a grain-only diet to produce meat. The meme I posted above with the wall of text attempting to explain the ratio (cuz “stupid bloodmouth meatards can’t read”) was wrong in making that claim. Pigs and chickens? Certainly. But cows? Nope. It isn’t very intelligent to think otherwise.

Feeding cattle grain is merely of convenience. It gets them to grow faster, fatter, and quicker to meet a constant, year-round demand for beef. Urbanization, capitalism, producing excessive grains, global export/import markets, and great marketing can be thanked for making that a new normal of the 20th and 21st centuries.

The reason is that cattle are ruminants. Ruminants have a much different digestive system than non-ruminants. Ruminants rely on forages and roughage (hay, silage, and even straw with limitations) to live to the fullest. They cannot live for very long on grain alone. This is why the finishing period for steers in the feedlot can only be a few months (four on average), not years. There are numerous ethical and welfare concerns around feeding ruminants nothing but grain for the long term, which is a cause for concern for farmers and animal activists alike.

Grass-fed beef is not only possible but practical. It takes longer, sure, but animals still get fat and big enough to be ready for slaughter. Management is key to getting good-quality, good-tasting beef that people will like to eat.

Smil said it quite well regarding grazing ruminants and competing with food for humans:

Grazing animals do not compete for phytomass with humans, and hence their growth does not pre-empt the use of any farmland for growing food crops, and their feeding efficiency is a key variable in proper grassland management but not in any calculation of potentially contested phytomass.

He also pointed out that there are three different types of feeding systems for beef production. One is grass-fed. The second combines grass-fed and grain-fed, where animals are grazed for anywhere from two months to over a year and spend between 120 to 170 days (or more than 200 days) in a feedlot until they reach their target slaughter weight. The third is being raised entirely in confinement. Daily gains are faster and heavier for animals in confinement versus grazing animals:

Limited mobility and concentrated feed result in much faster daily gains, as much as 1-1.4 kg [2.2 -3.1 lb] compared to less than 500 g [1 lb] for grazing cattle.

Smil reasoned then that it’s difficult to adjust feed conversion rates to reflect only the consumption of grains (concentrates), and they can compare to how pigs and poultry are fed. He says:

Beef production in all affluent nations combines forage and concentrate feeding in a variety of practices that differ not only among countries but also among regions and that change with prices of concentrate feeds and with the abundance of grazing phytomass.

Breeding beef cattle (bulls, cows, heifers) often consume diets largely forage-based (90% or more), with grains and concentrates only acting as supplements to cover what forages cannot. It’s the reverse with finisher market cattle (primarily steers and some heifers).

In saying all that, the claim meme number two of this topic makes:

A cow eats about 12 kg of grain per day

…is incorrect. But it’s also correct only when the context is understood. Twelve kilograms (26.5 pounds) is a lot of grain to feed a ruminant daily. That amount of grain is only for two purposes: fattening cattle for slaughter and feeding lactating dairy cows raised in confinement. Other cattle classes are fed much less than that or no grain at all.

When grain is needed for cattle, it’s so that they can gain weight (or keep it on) when fed roughage that is poorer in quality than what a farmer desires for his/her animals and so they can keep warm and healthy during the cold of winter. The amount needed varies from farm to farm. Some farms may only need to feed a pound (0.45 kg) per cow daily or up to over 15 pounds (7 kg) daily. Rarely is more needed. (Note: this is for the aforementioned breeding beef cattle, which comprise the majority of North America’s beef cattle population.)

However, this still fails to explain how 16 kg of grain per kilogram of beef came about. That’s where we need to turn to Lappe’s book and the sources she used to come up with this ambiguous, almost random number that so many activists love to repeat.

Lappe’s Claims and Answering How She Did It

It was interesting to read about Lappe’s Diet for a Small Planet and her discoveries about conventional agriculture and food. She talked about her journey in the 1960s and 1970s and shared many facts about industrial animal agriculture that she found in her research.

While I didn’t agree with a lot of what she said, at least I know now where so many vegans got their anti-animal agriculture statistics from.

I want to bring to your attention her discovery in the first part of the book:

In 1969 I discovered that half of our harvested acreage went to feed livestock. At the same time, I learned that for every 7 pounds of grain and soybeans fed to livestock we get on the average only 1 pound back in meat on our plates. Of all the animals we eat, cattle are the poorest converters of grain to meat: It takes 16 pounds of grain and soybeans to produce just 1 pound of beef in the United States today.

—

Lappe, Frances Morre. Reprint 2021. Diet for a Small Planet. Ballantine Books Publishing. Book 1, Part 2, Chapter 1: pg. 9

There are no sources for this (curious), but she reveals more details as I read further into the next chapter.

But before I get into that, this part is essential to keep in mind for the rest of this post:

Instead of going from pasture to slaughter, most cattle in the United States now first pass through feedlots where they are each fed over 2,500 pounds of grain and soybean products (about 22 pounds a day) plus hormones and antibiotics.*

—

Ibid. Part 2, Chapter 2: pg. 68

Her footnote for that statement [*] said the following:

The amount varies depending on the price of grain, but 2,200 to 2,500 pounds is typical. See footnote 13 [see below] for more detailed explanation of grain feeding.

—

Ibid. Notes: pg. 371

Returning to Chapter 2 of Part II of the book, we again get to read the statistic, this time with the superscript to check out Footnote 13:

For every 16 pounds of grain and soy fed to beef cattle in the United States we only get 1 pound back in meat on our plates. The other 15 pounds are inaccessible to us, either used by the animal to produce energy or to make some part of its own body that we do not eat (like hair or bones) or excreted.

—

Ibid. Book 1, Part 2, Chapter 2: pg. 69

Now, before we get into her calculations, I want to answer the question (one that I sure had many times when reading these): where in the heck did she get her sources? Well, this is where, at the very bottom of Footnote 13:

These estimates are based on several consultations with the USDA Economc Research Service and the USDA Agricultural Research Service, Northeastern Division, plus current newspaper reports of actual grain and soy currently being fed.

—

Ibid. Notes: pg. 372

Okay, I guess I’ll give her some kudos for looking like she did her research. Yet, it’s too bad it’s not sources that are reasonable to access, like library books or sources on the Internet (I know, I know, the Internet wasn’t available back in the 1970s). (Spoiler alert: We’ll soon see why such sources weren’t exactly available…)

Let’s now examine Footnote 13 to see how she did her calculations.

How many pounds of grain and soy are consumed by the American steer to get 1 pound of edible meat?

a) The total forage (hay, silage, grass) consumed: 12,000 pounds (10,000 pre-feedlot and 2,000 in feedlot). The total grain- and soy-type concentrate consumed: about 2,850 pounds (300 pounds grain and 50 pounds soy before feedlot, plus 2,200 pounds grain and 300 pounds soy in feedlot). Therefore, the actual percent of total feed units from grain and soy is about 25 percent.

b) But experts estimate that the grain and soy contribute more to weight gain (and, therefore, to ultimate meat produced) than their actual proportion in the diet. They estimate that grain and soy contribute (instead of 25 percent) about 40 percent of weight put on over the life of the steer.

c) To estimate what percent of edible meat is due to the grain and soy consumed, multiply that 40 percent (weight gain due to grain and soy) times the edible meat produced at slaughter, or 432 pounds: 0.4 x 432 = 172.8 pounds of edible portion contributed by grain and soy. (Those who state a 7:1 ratio use the entire 432 pounds edible meat in their computation.)

d) To determine how many pounds of grain and soy it took to get this 172.8 pounds of edible meat, divide total grain and soy consumed, 2,850 pounds, by 172.8 pounds of edible meat: 2,850 x 172.8 = 16 – 17 pounds. (I have taken the lower figure, since the amount of grain being fed may be going down a small amount.)

—

Ibid. pg. 371-372

At first glance, and to the untrained eye, these values seem difficult to debunk because they appear well-researched and realistic. However, when I crunch the numbers, there are an alarming number of details that are very concerning—and I do mean VERY concerning!

It’s time for some debunking!

Testing Lappe’s Calculations Using Real-Life Beef Nutrition Calculations

The best place to start is the carcass weight. Lappe estimated that the carcass weight (note she called it “edible meat produced at slaughter,” which must mean carcass weight, and not trimmed boneless cuts from that carcass, which is “retail weight”) is about 432 pounds. When I calculate “up” to get the liveweight (where the carcass weight is around 60% of the liveweight of an average American steer), I come to (0.6 / 432 pounds carcass weight =) 720 pounds liveweight.

Hmmm. That’s nearly half the average liveweight of a finished market steer. On average, according to the USDA, a market steer at slaughter is around 1,300 pounds, not 720 pounds.

Smil mentioned a feedlot steer being slaughtered at 530 kg (almost 1,200 pounds) above. That’s still heavier than Lappe’s estimate and much closer to the national (and international, as Canadian slaughter steers are finished and slaughtered to a similar) average.

But let’s continue working with the small 720-pound finisher steer.

Here’s what we don’t know that we, quite honestly, should know:

- Age at slaughter.

- The expected or actual ADG (average daily gain), particularly on average.

- Weaning weight and weaning age.

- Length of the so-called “pre-feedlot” (I much prefer backgrounding and will use that term from now on) feeding period

- Length of the feedlot-finishing program.

- Liveweight at slaughter (I can only assume by doing calculations.)

These details are crucial (for me, at least) because they provide a stronger platform to check if Lappe’s calculations are way out to lunch or relatively realistic.

Whether Lappe left those details out due to convenience or deliberation is irrelevant. However, it forces me to make a lot of wild-ass educated guesses based on current sources I have at my disposal. And I don’t like to make assumptions because they may or may not be correct, especially in what Lappe was hoping to achieve!

But, assumptions I must make. Thanks, Lappe.

The Questions of Age and the Feeding Period… Assumptions to be Made

The feeding program for any market/beef steer doesn’t begin until post-weaning. Most are weaned at around 5 to 6 months of age, weighing around 500 to 600 pounds. Based on the low finishing weight, I guess this steer was weaned at 450 pounds at 5 months old—small weaning weight: small finishing weight. Makes sense, I guess?

Calves, while on their mothers, don’t start eating much feed until they’re a month or two away from weaning, and even then, the amount they eat is considered statistically insignificant. This is why knowing weaning age is relevant. Weight at weaning is more critical because this is the starting point for the growing and feeding program. Age at weaning only allows us to determine how old a steer is at slaughter. (It’s of greater relevancy when I’m working on feed rations and have to know the age of the animals I’m formulating rations for.)

Thus, we can assume that the difference in weight from start to finish is 720 – 450 = 270 pounds. This steer possibly gained 270 pounds in body weight up to slaughter.

Now, what about the steer’s age when killed? The age at finish for grain-fed cattle ranges from 12 months to over 22 months. (“Prime” steers & feeder heifers are fed for longer, not being slaughtered until 30 to 42 months of age.) I’m assuming the steer may have been a year old, which means the feeding period is assumed to be (12 – 5 =) 7 months long.

Converting seven months to days (7 months x 30.5 days/month) gives us 213.5 days of feeding.

(We’ll see very soon how far off base that is!!!)

First Assumption to ADG (Average Daily Gain)… Am I Right??

Typically, the expected ADG for a feeder steer should be between 2 to 3 pounds a day (between 1.5 to 2.25 lb/day for backgrounding and 3 to 4 lb/day in the feedlot). But is that what this steer is actually gaining, according to Lappe’s arithmetic??

To find out, we take the 270 pounds gained throughout the feeding period and divide that by my estimated feeding period (213.5 days). The result is a dismal 1.26 pounds/day. (Unrealistically lower than average. Ick. Must’ve been a thin, sickly steer that was killed.)

How Much Feed Does Lappe’s Example Steer Eat?

Using Lappe’s total feed amount, which is 14,850 when combining both forage and concentrate amounts of both backgrounding and feedlot (12,000 pounds of forage + 2,850 pounds of concentrate), the steer is assumed to consume (14,850 pounds total feed / 213.5 days total feeding period =) 69.55 pounds of feed per day.

Jesus Christ, NO!! No, no, no, no, no!!

That’s almost five times the average amount that little steer can eat daily!!

Here’s my proof: A steer should be eating 2.5% of his body weight per day. So, when he started on feed, this steer was eating (500 x 2.5% =) 12.5 lb/day. At the end of his feeding period, he should be eating (720 x 2.5% =)18.0 pounds per day.

See what I mean? Almost five times the amount. Yikes.

Let’s look at it this way: How big does a bovine (cow, bull, steer, whatever) must be to eat nearly that amount: 70 pounds of feed daily?

Well: 69.55 pounds per day / 2.5% = 2,780 pounds. That’s a BIG animal.

Time to Fess Up: The Math Doesn’t Jive!

Okay, Lappe. Did you really consult those USDA economists, as you claimed? Be honest. Nothing is adding up; nothing is making any sense. Did you add a zero by accident? Mishear what they told you? Or did you just make things up, assuming nobody will notice or bother to sit down and double-check your work?

Also, why in the feck did you NOT consult a beef nutritionist???? Why economists?? They know almost next to nothing about beef nutrition and often have to consult with animal nutritionists to make sure their numbers are correct. And yet you didn’t. Why??

I mean, I can forgive the smaller-than-average slaughter weight, sure, because there are animals that do get slaughtered at that weight (it’s called “veal” or “baby beef”).

But the amount of feed YOU claimed was “legitimate” for this tiny little dude to eat PER DAY, to get THAT LOW of a slaughter weight coupled with a whole lot of missing information??? Come on!!

I know, I know. Some of you might argue that I’m proving nothing and detracting away from debunking Lappe’s ratio. But I’m sure you can’t debate the elephant in the room: It’s really important to get the numbers right for credibility’s sake.

Skew any numbers, and you get a dishonest, discredible statistic that deserves to be challenged, questioned, and debunked. Be honest with the numbers; the result will be truthful, credible, and inarguable. It’s that simple.

Further Testing for Feeding Period, ADG, and Ration Percentages

Now, let’s assume we don’t know the feeding period (unlike above). I need to do two things to figure that out:

- Calculate the average weight of the steer from start to finish, and

- Calculate the amount of feed that steer should be eating on a daily basis.

The average weight of this steer from start to finish is (average calculated as (720 + 450) / 2 =) 585 pounds.

He is expected to eat around 2.5% of his body weight daily. So he should consume (585 pounds x 2.5% =) 14.6 pounds/day.

Therefore, if that steer is to consume 14,850 pounds of total feed from weaning to slaughter, the finishing period is (14,850 / 14.6 =) 1,017 days or (1,017 days / 30.5 days/month =) ~33.3 months. Therefore, this tiny steer was 38 and 1/3 months (or 3.2 years) old when he was slaughtered.

The new ADG value would be (270 lb gained overall / 1,017 days of feeding =) 0.265 pounds/day.

That’s disgusting.

No young, growing animal should be allowed to gain at that low of a number, whether it’s for meat, for breeding, or even kept as a pet. (I doubt any animal sanctuary would consider that growth rate humane, even if they don’t value its relevance in their care for the animals they take in. At least, I hope not.)

(For those of you wondering what “average daily gain” or ADG means, it’s an industry term that refers to the weight gain over one day that a heifer, bull, steer or cow will have on a certain type or mix of feed. Weight gain is in terms of gaining muscle, fat, bone, or overall body mass. ADG is essential in growing meat animals because it helps farmers to know what (or not) and how much can be fed to get the desired growth, gain in muscle mass and fat cover up to slaughter.)

But wait! There’s more!

Let’s see how accurate Lappe’s make-believe rations are compared to real-life backgrounding and feedlot rations.

(Spoiler Alert: Lappe’s calculations are, once again, extremely inaccurate. Shocker.)

As we read above, Lappe divided the total amount consumed into backgrounding and feedlot rations. Then, she divided the amounts into forages and grain concentrate (or grain and soy).

Concentrates make up 85 to 90% of feedlot rations. Cattle entering the feedlot start on 40% grain and gradually increase to 90% concentrate over a month or so.

The concentrate portion typically makes up 25% of the backgrounding ration. However, some operations prefer 40% for faster gains.

For the backgrounding diet, she gave us 10,000 pounds of forage plus 350 pounds of grain/soy, which makes 10,350 pounds of total feed consumed. Dividing 350 pounds by 10,350 pounds reveals that grains make up 3.4%.

For the feedlot diet, she gave us 2,000 pounds of forage plus 2,500 pounds of grain/soy, for a total of 4,500 pounds of feed consumed. Dividing 4,500 pounds by 2,500 pounds gives the concentrate portion of the ration at 55.5%.

Shameful. We can’t take Lappe’s numbers seriously by any stretch of the imagination.

The only thing I can take into consideration is her methodology in how she made her calculations. This is about the only good thing she did for us. We can use that against her to prove whether this 16:1 ratio is complete horseshit or somewhat realistic.

How Much Does an Average American Steer Really Eat from Weaning to Slaughter?

These are the average values we understand for the average American steer from the start of the feeding period (post-weaning) to slaughter:

- Weaning age: 6 months old

- Weaning weight: 500 pounds

- Slaughter age: 20 months old

- Slaughter weight: 1300 pounds

- Expected ADG range during the backgrounding phase: 1.0 to 2.25 pounds/day

- Expected ADG range during the finishing feedlot phase: 3.0 to 4.0 pounds/day

- Total feeding period in months: (20 months old at slaughter – 6 months old at weaning =) 14 months of feeding

- Feeding period in days: (14 months x 30.5 days/month =) 427 days

- Average time spent in the feedlot: 4 to 6 months; range is 3 to 12 months

- Length of backgrounding period: ~10 months (or 305 days)

- Length of finishing feedlot period: ~4 months (or 122 days)

We can (fairly) easily determine the feed consumed throughout both periods using these values. However, the two most significant influences when working out the calculations are average daily gains (ADG) and the number of days on feed. More on that below.

Even though it’s more work, using Lappe’s calculations, which we tore to shreds above, is the best way to figure out this ratio. So, we’ll follow that methodology to demonstrate how close, far, or highly variable this ratio can get.

If we stick with ballpark average values, it’s fair to know that this steer is around 900 pounds when he enters the feedlot. (How did I get that? Figure about 1.3 pounds/day ADG x 305 days, and use a rounded figure.) Therefore, the average total feed consumed overall is:

- Average weight during backgrounding: (500 + 900)/2 = 700 pounds

- Feed consumed per day (backgrounding): 700 x 2.5% = 17.5 pounds/day

- Feed consumed (backgrounding): 305 days x 17.5 pounds/day = 5,337.5 or ~5,300 pounds of feed

- Average weight during feedlot: (900 + 1300)/2 = 1,100 pounds

- Feed consumed per day (feedlot): 1,100 x 2.5% = 27.5 pounds/day

- Feed consumed (feedlot): 122 days x 27.5 pounds/day = 3,355 or ~3,300 pounds of feed

- TOTAL feed consumed: 5,300 pounds (backgrounding) + 3,300 pounds (feedlot) = 8,600 pounds

It’s amusing how much less the amount of feed consumed over just 14 months is compared with Lappe’s numbers, isn’t it?

But, we still have to calculate the grain concentrate portion.

To calculate the amount of grain concentrate consumed per type of feeding period, we need to use average percentages of forage roughage versus grain concentrate.

As discussed above, concentrates comprise 85 to 90% of the diet in the feedlot ration and 25% in backgrounding rations.

The total feed consumed in the backgrounding phase is about 5,300 pounds. Multiplying by 25% gives about 1,325 pounds of that ration comprised of grain (and/or soy). The amount of forage consumed is (5,300 – 1,325 =) 3,975 pounds.

The total feed consumed in the feedlot phase is 3,300 pounds. Multiplying by 90% gives 2,970 pounds of that ration comprised of grain (and/or soy). The amount of forage consumed is (3,300 – 2,970 =) 330 pounds.

That’s a total of (1,325 + 2,970 =) 4,295 pounds of grain, and (3,975 + 330) = 4,305 pounds of forage consumed throughout the entire feeding period.

Now, with these much more accurate values, can we debunk her 16:1 ratio? Can we prove that the meme is completely inaccurate? It’s time to find out!

What is the More Accurate Ratio of Grain Consumed Per Pound of Edible Beef?

We know that the live weight of our American steer at slaughter is 1300 pounds.

The carcass weight, 60% of the liveweight, is then (0.6 x 1300 =) 780 pounds.

The retail meat weight, 40% of the carcass weight, is (0.4 x 780 =) 312 pounds. According to Lappe, this is the “edible meat” portion of her equations.

Therefore, the amount of grain consumed per pound of edible meat is (4,295 / 312 =) 13.77

I know this isn’t a significant difference from what Lappe got, but I’ll argue that it’s far more truthful in how it was obtained. It gives far more credibility and legitimacy to how it was obtained, which cannot be said for how Lappe did it.

But I digress.

Something interesting I found is that this ratio will change not just with shifting slaughter weights and the length of time a steer is fed for slaughter but with how long they are kept in the feedlot (or being backgrounded) and the changes in average daily gains.

How does that work? Let’s discuss that next.

How the Ratio can be Changed

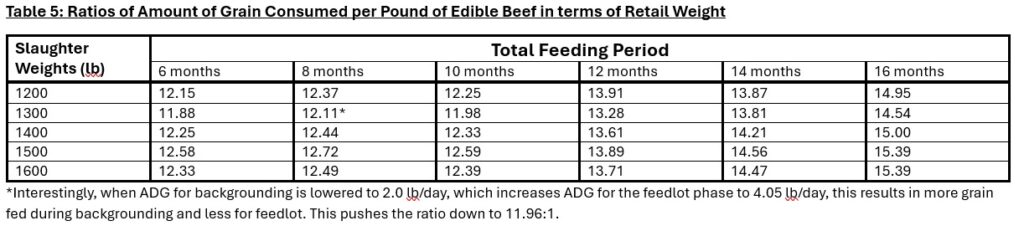

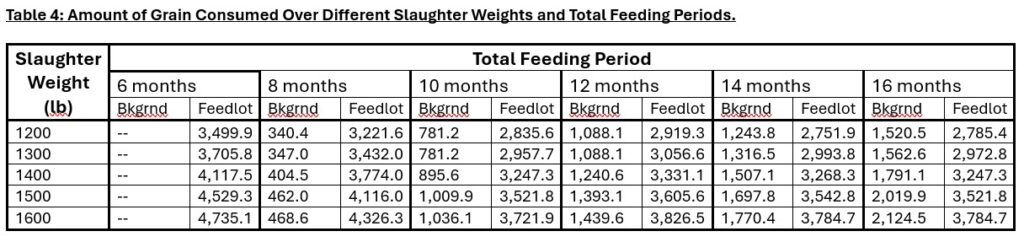

Let’s take a look at this table I developed just for shits and giggles.

(If you have any questions about this table, please comment below.)

What’s obvious is that lower slaughter weights infer a lower ratio. And, the longer the feeding period, the higher the ratio.

I think we can all expect that, right?

I know you’ll notice quite a few discrepancies in the table above, where what I just mentioned isn’t always the case. Allow me to leave a couple more tables below to discuss that next.

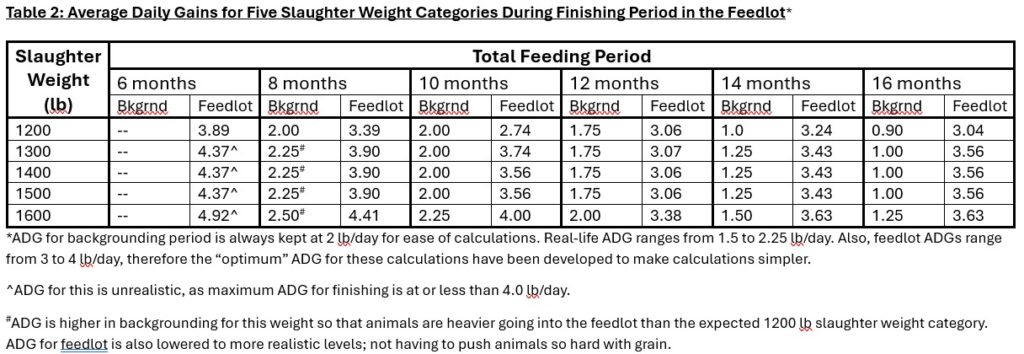

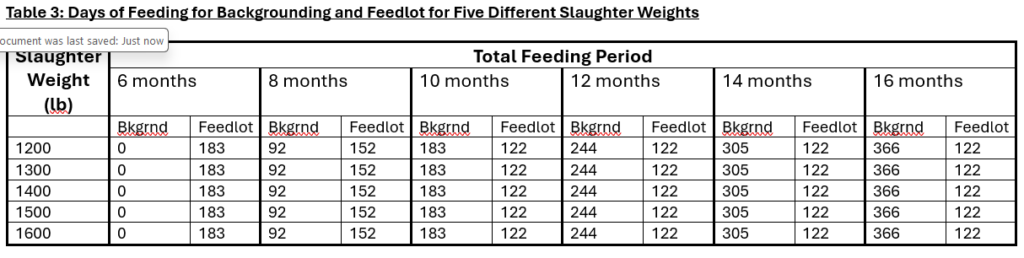

In Table 3, you’ll notice that I’ve kept feeding periods as consistent as possible for five slaughter weights: 1200 pounds, 1300 pounds, 1400 pounds, 1500 pounds, and 1600 pounds. However, they can be changed; they’re not set in stone.

You’ll also notice that the most efficient feed conversion happens when steers are fed to a 1300-pound slaughter weight. While it’s beyond my pay grade to understand why (perhaps someone smarter than me can explain, and if so, please do, as I’d love to hear the science behind it), it’s an interesting observation.

(Maybe this is a good reason I chose 1300 pounds as my first example above… hmm! Interesting!)

Table 4 shows the ADG or average daily gains. I noted that some of my examples (particularly during the six-month feeding period) were a bit out-to-lunch with ADG. Pushing animals above four pounds per day gain is hard on them and next to impossible. But they’re just numbers, and only created for curiosity’s sake.

However, as noted in Table 5 above, their influence influences the ratio regarding how much grain a steer may consume overall.

If I changed the ADG backgrounding to 2.0 (instead of 2.25) for a 1300-pound slaughter weight steer fed over 8 months, the total grain consumed would be 340.4 pounds. The ADG feedlot would bump to 4.05 lb/day (to compensate for the lesser weight gained during backgrounding), and the grain consumed would decrease to 3,392.6 pounds. Therefore, the ratio becomes (340.4 + 3,392.6)/312 = 11.96 pounds of grain consumed per pound of edible beef.

(Recall that the pounds of edible beef for a 1300-pound steer is about 312 pounds: 1300 lb x 60% carcass = 780 lb carcass weight x 40% retail = 312 lb retail weight.)

If I went the opposite way, changing the ADG backgrounding to 1.75 lb/day (same slaughter weight goal, same feeding period), the feedlot ADG would bump to 4.20 lb/day. Grain consumed over backgrounding is 333.8 pounds and 3,353.6 pounds over the feedlot period. The resulting ratio is (333.8 + 3,353.6)/312 = 11.82 pounds of grain consumed per pound of edible beef.

Again, the problem is that the ADG for feedlots is getting unrealistically high. Yes, grain conversions seem to get “better” (on paper), but that’s unrealistic.

What makes it more realistic (but increases the ratio) is when I change the background feeding period from 92 days to 62 days and the feedlot period from 152 to 182 days. The amount of grain consumed during the backgrounding phase is 217.8 pounds, and for the feedlot phase, 3,939.4 pounds. That makes it (217.8 + 3,939.4)/312 = 13.32 pounds of grain consumed per pound of edible beef.

Another example is if this 1300-pound steer is fed over 14 months (427 days), and we have him to be backgrounded for 365 days (1 year or 12 months) and finished over just two months (~62 days), with an ADG (backgrounding) of 1.5 lb/day and (feedlot) 4.05 lb/day, grain consumption is 1,765.1 lb (backgrounding) and 1,637.4 lb (feedlot). This results in a ratio of 10.91 pounds of grain per pound of edible beef.

That’s not surprising one bit—the less grain consumed over the entire feeding period, the lower the ratio becomes.

On the other hand, the more grain consumed, the higher the ratio. Perfectly logical. And, it reflects what Smil discussed above.

Here’s my proof of yet another table to share (whoopee):

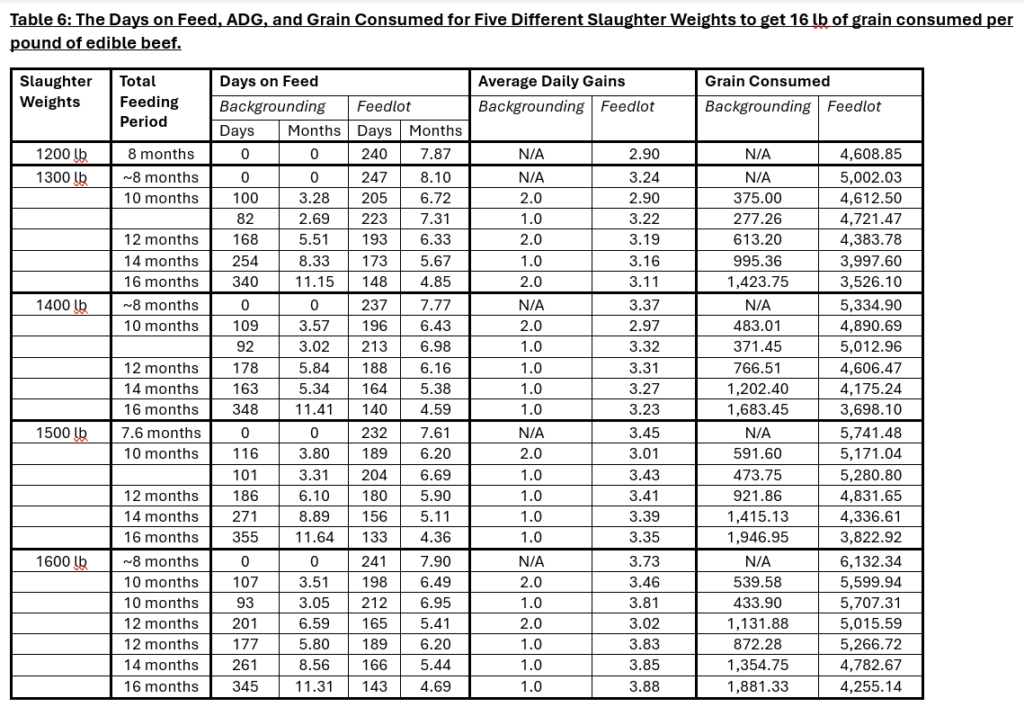

But I was curious to know what it takes to get that 16:1 ratio. So, I crunched more numbers.

Want to see them? Great, so do I!

Getting the 16:1 Ratio by Realistic Means

I’ll be honest: there is no single way to get to that ratio. Not a one.

As already mentioned, we’ll stick with our ADG goals for consistency (and less work for me to do). The only things that will be changed considerably are slaughter weights and feeding periods.

So, rather than boring you to death (if you’ve made it this far) with all the scenarios, how about another table to look at?

Some may think this proves the 16:1 ratio correct. And you’d be right; it does.

However, the actual time that steers stay in the feedlot varies:

Depending on their arrival weight, cattle may spend anywhere from a few months to nearly a year in a feedlot. Typical feedlot stays are slightly less than 6 months.

U.S. Feedlot Processing Practices for Arriving Cattle. APHIS Info Sheet Veterinary Services. Link: https://tinyurl.com/22xrf6xq

Cattle in Canadian feedlots spend around the same amount of time, all things depending:

Cattle in Canada spend most of their lives on pasture while only spending 60 to 200 days in a feedlot.

Alberta Cattle Feeders’ Association. What Goes On in a Feedlot? https://cattlefeeders.ca/feedlot-101/

According to the USDA Economic Research Service, cattle stay anywhere from 90 to 300 days in the feedlot.

How long cattle stay in the feedlot depends on how much weight they have to gain. This is why contention around this 16:1 ratio is deserved, as it’s not guaranteed to be truthful.

Especially when a meme like this has a few more issues that must be addressed.

More Major Issues with the Meme

A few issues to discuss (I’ll try to be brief as this is already a very long post) are around the wording of “grains,” the use of wheat as a stand-up example, some DYK on corn and soybeans, issues on feeding grains to people, how much grains people will eat in realistic terms, and how much beef people will eat on average.

Mind the Word “Grains”

Grain comes from a lot more than just corn. There’s wheat, barley, oats, rye, triticale, rice, sorghum, and millet. Livestock can be fed any of these types but are most commonly fed corn, barley, triticale, and oats, which are not necessarily in that order.

Using Wheat as a Stand-Up Example is Wrong

The meme used a wheat stalk graphic to imply that wheat is used as a primary feed source. This is wrong on many, many levels.

Wheat is a much “hotter” feed than either corn or barley. By that, I mean it is very easily digestible by the rumen microbes. This seems good to most people, but it’s not for rumen microbes. This is because the starch component is very easy for them to access and break down.

Never mind that it takes a long time (about a month) for those microbes to adjust to this type of grain. The fact remains that wheat’s very high digestibility causes metabolic issues like acidosis, bloat, and even founder if too much is given. Acidosis and bloat are often deadly if not caught right away and treated promptly.

Wheat must be limit-fed; it cannot make up more than 40 to 50% of the grain mixture (not the daily ration) to animals on high-grain diets (like finisher cattle and dairy cattle). It cannot make up more than 20% of the ration for beef cows and heifers. Finely chopped or ground wheat cannot be fed to cattle; whole or coarsely rolled is better. Finely processed wheat is a trainwreck waiting for a place to happen. [Source: Manitoba Agriculture]

Wheat is only available for use as cattle feed if it hasn’t met the “human grade” grading standards. Weather, pests, disease, and poor storage practices causing heated or sprouted grains result in this.

About Feeding Corn and Soybeans to Cattle

Corn is commonly fed in the United States because it grows well there. Its slow rate of starch digestion makes it ideal for feeding ruminants. Plus, grain markets, government subsidies and its high popularity make it a “have-to feed” as opposed to a “must feed” (in the United States, at least) based on availability to farmers.

If any of that made any sense!

But there’s a problem. Corn generally contains 8 to 9 percent crude protein, which is lower than the protein requirements for most beef (and dairy) cattle. Soybeans, another highly popular pulse crop in the ‘States, cover that base quite easily.

Soybeans are a high-protein source. Raw or unroasted soybeans contain about 40% crude protein and 20% fat. Sounds good, right? Sure, but for ruminants, it’s a lot. They cannot account for more than 7% of the daily ration for cattle. If they eat any more than that, they could get sick or die of bloat or acidosis.

Besides, chickens and pigs eat far more soy than cattle do. Their digestive systems are built differently, making them able to handle more grains (and richer sources) than ruminants.

Feeding Grain to Cattle in Canada

Here in the north (Western Canada), barley is more commonly fed than corn. Barley contains 11 to 12% crude protein, which just meets the minimum protein requirements for feeder cattle that are almost a year old. Some protein supplements may be used if the barley was tested to be of poorer quality than desired, such as wheat dried distillers grains (DDGs), peas, faba beans, or canola meal.

We can’t grow corn or soybeans in enough quantities for grain up here to substantiate their use in our northern feedlots. They don’t do well with such short growing seasons or a colder climate. Shipping them from the US is far too costly; it’s much cheaper to buy (or grow) what is grown locally. If we are to grow corn (which we have in the past 15 years), it’s only for silage or for grazing beef cows in the winter.

It’s a much different story for Eastern Canada (Ontario and Quebec). That part of Canada has perfect growing conditions for those two crops. However, most of the beef in Canada is raised in Alberta and Saskatchewan.

Issues on Feeding Grains to People

People cannot eat grain the same way cows, chickens, pigs, or other animals can. Grains must be processed in multiple stages to be edible.

Wheat can’t be fed whole; it has to be milled and ground into powder (flour) for pasta, bread, and pastries.

Corn has to be turned into various edible constituencies (many done so in a lab) to be constituted into foods from Twinkies to breakfast cereal. “Vegetable” corn must be harvested at the right stage to be edible as corn-on-the-cob or “fresh” frozen corn for a side dish. And, the corn itself can’t be just any corn: it has to be the right, sweet-tasting variety (no doubt there’s more than one) for people like you and me to like to eat!

The same goes for other grains: they, too, must be processed to an extent to be edible for cereals, bread, granola, porridge, vegetable oils, and many other dishes. These include oats, barley, millet, rice, sorghum, soy, and pulses (lentils, peas, chickpeas, etc.).

The average human eats around three to four pounds of food a day. Keep that in mind for these next couple of parts.

How Much Grain Do People Eat on Average?

A quick Google search shows that the average person (adult) is expected to eat between 5 to 8 ounces (or ounce-equivalents) of grain daily. That’s one-third to one-half a pound per day.

In other words, at most, a quarter of our diet is recommended to include grains. That’s not even close to the percentage of grains that make up the diet of ruminants on a high-grain diet, which is 50 to 90%. (But, it depends on the person and the diet they/she/he so chooses to eat.)

According to the meme, 16 kilograms of grain provides one meal for 20 people.

That’s A LOT of grain to eat in one sitting. Sixteen kilograms converts to 35.2 pounds. That means people are (basically forced) to eat 1.76 pounds of grain in one meal. How outrageously ridiculous is that??

The featured meme (the yellow one without the wall of text) says it feeds 20 people. That’s still 1.76 pounds of grain per day, or 44 to 57% of the diet, which is a lot of grain. Nobody really should eat that much grain, even in one day.

I hate to say it, but 35.6 pounds of grain should feed a lot more people than just 20 gluttonous freaks. Based on nutritional recommendations, it really should feed 89 people.

Let’s look at the meat side of the equation.

How Much Meat Do People Eat on Average?

According to Wikipedia, the average American consumed 124 kilograms (or 273.4 pounds) of meat per year in 2020, which is 0.75 lb (or 0.34 kg) per day. This means that 1 kg of meat, per the meme[s], feeds three people (if they eat as much as the average American) per day.

In 2020, the average Canadian consumed 82.6 kg (182 lb) of meat per year, which is 0.5 pounds (0.226 kg). This means that 1 kg of meat, per the meme[s], feeds 4+ people daily.

General recommendations say that the average person should consume 2.5 servings of meat per day. One serving is 3 ounces, meaning a person should consume 7.5 ounces or 0.469 pounds daily. That means 1 kg of meat, per the meme[s], would feed nearly five people daily.

The meme is inaccurate in this department as well. Shocker.

How Do Grains Compare to Meat Nutritionally?

Grains can’t compare to meat nutritionally. It’s preposterous to claim otherwise.

Grains are high in calories (energy), which counters most other nutrients when created as bread. Calories, a measurement of energy, also known as carbohydrates, present at too high levels in the body and cause issues like obesity, fatty liver, metabolic issues, etc. Modern grains have become known to cause problems like gluten sensitivity, celiac disease, Crohn’s, and others.

Beef is high in essential amino acids, essential fatty acids, and other important vitamins and minerals. Bread has some minerals and vitamins, but those carbohydrates get in the way.

So, those 89 people who get the grain instead of beef are on the losing end. Or they’ll use that grain for bread and eat it with other foods, including meat.

Debunking More BS Related to the Meme

Some anti-meat “critics” like to claim:

… there is no biological or nutritional requirement for humans to consume animals or their bodily secretions.

—

From 80spopanimals.com Vegan Resources: Human Hunger & Starvation. Link: https://www.80spopanimals.com/veganresources

Yes, there is. Humans need meat, dairy, and eggs for nutritional health because they are biologically appropriate staples of the diet.

We don’t have multi-chambered forestomach or cecum to properly and completely digest plants, and our large intestine isn’t as robustly developed as a gorilla’s (as many vegans love to compare us to). Plants pass quicker through our digestive system and come out less digested than animal products. It’s not meat that rots in our colon; it’s plants like beans, corn, kale, and other difficult-to-digest edible plants that do.

It explains why we all get pretty gassy after eating a meal primarily of vegetables. You don’t get that problem if your meal is mostly meat, as many “carnivores” can testify to.

Surmounting evidence (albeit anecdotal) shows that the long-term effects of a vegan diet have significantly harmful, long-term impacts on the human body: impacts that people have to live with for the rest of their lives. Millions of both vegans and ex-vegans have reported things like their hair falling out and losing its lustre; their teeth getting poorer in condition and even falling out; feeling fatigued more often and experiencing low energy; sudden negative emotions for no apparent reason like anger, depression, and irritation; acne and other skin issues; increased risk of breaking bones and osteoporosis (despite them claiming dairy is the sole cause); exacerbation of IBS symptoms and other digestive problems that don’t seem to go away no matter what they try to do with their diet and continue to avoid animal products at all; anemia; infertility, erectile dysfunction, loss of natural menstruation cycling, and other reproductive issues; risk of liver and kidney disease; the list goes on and on.

All of these people (ex-vegans primarily; vegans continue to live in denial) have found that, after eating even a small portion of animal products like a single egg, some cheese, or even a small helping of chicken, they felt significantly better health than they thought possible. They felt happier, and eventually, their health problems, which they thought they could never imagine having on a vegan diet but did, went away after eating animal products.

Over 84% of vegans and vegetarians return to normal omnivory. An untold percentage of people (likely well over three-quarters) that turn vegan go back to omnivory a year or less later. I’ve no doubt many “vegans” are also cheaters who succumb to intense cravings for animal protein in secret.

A cow’s diet requires much more vegetation than a human diet. An adult cow can weigh from 1,600 to 2,400 pounds (726 to 1,089 kilograms). One acre of land can produce 2.5 pounds (1.134 kilograms) of animal flesh OR over 24,000 pounds (11,188 kilograms) of edible plants. Vegans eat plants directly rather than having massive amounts of crops fed to fatten up animals who are later eaten by humans.

—

Ibid, above.

Yet, vegans are not cows. Vegans are still humans. They just hold fanatical beliefs that they can do better than anybody else, don’t need cows or any animal to thrive or survive, and are the healthiest humans on the planet. (Yet that tiny part of the human population (only around one to two percent) has plenty of evidence to show, as pointed out above, none of that is true. Acting like you’re better than everyone else is a toxic negative mentality that harms you and those around you.)

Yes, cows eat far more vegetation than humans, but is that really an issue we should be concerned about? No.

Let’s be completely honest: 70 to 100 percent of a cow’s diet comprises vegetation that no human would eat. Not even a vegan. Claiming otherwise is foolhardy and calls for you better to educate yourself on cow nutrition and digestive physiology!

An adult Holstein cow will weigh that much, but what about other breeds? The world isn’t covered in just Holsteins. Many adult cows and cattle in the world range in weight from 500 pounds (250 kg) as miniature breeds to over 1,100 kg. It depends on the breed.

That one acre of land statistic, however, is infuriatingly wrong. That one acre can yield SO MUCH MORE than that piddly pathetic 2.5 kg of meat. Multiple sources show that one acre can yield between 1,000 to almost 3,000 kg (2,000 to 6,000 pounds) of meat. It depends on the land and how much forage can be grown to feed those animals. (Only on poorly managed land or near desert would 2.5 kg of meat be produced on an acre.)

What is correct is that at least twice to ten times the amount of vegetation can be grown on that same piece of land. But that still doesn’t mean that vegetation can be saved for humans only and not shared with animals.

Sometimes people say that not all land can be used for growing crops. If that is true, then how is it possible that we are currently feeding tens of billions of animals enough plants for them to become human food every year? Humans can eat those same plants, and humans require far less than cows and other animals…

—

Ibid, above.

To answer that question, around 86 percent of what livestock eat (pigs, cattle, poultry, and other animals) isn’t suitable for human consumption. That’s how. Also, much of the grain fed to livestock is locally grown because shipping costs (including tariffs and inspection to ensure it meets specific national standards) for getting feed from other countries are insane. It’s much cheaper for farmers to buy (or grow) feed locally rather than rely on feed grown and harvested thousands of miles away.

Also, land that cannot be used for growing crops grows vegetation on which only certain animals with specific digestive systems designed to eat those plants can be raised. That land may also have rough terrain and thin, rocky, sandy, or poor soil, which makes growing crops impossible. Alternatively, that same land can be acceptable for growing crops, but not conventionally. Instead, its production requires a great diversity of plants and the incorporation of animals to keep it healthy.

When land is farmed, it is purposed for the growing of vegetation. That vegetation may go to feed humans, animals, or even both. Farmers often do crop rotations where they grow a different crop yearly or a mixture of various species. There are multiple reasons for doing this. One main reason is to benefit the soil and improve its fertility and quality. Others are to combat weeds, encourage livestock on the land (for soil health), take advantage of a market opportunity, encourage pollinators, and so on.

Land, therefore, isn’t solely used for one thing in agriculture. One year, it can be used to grow wheat; the next, it can be planted to forage to graze cattle. Cattle may be put on the wheat field after the harvest to add fertility and clean up what waste was left behind by the combine harvesters. This is very similar to market gardens that don’t have cattle but small livestock like chickens, ducks, pigs, or sheep.

Animals greatly benefit the production of grains, fruits, vegetables, nuts, and oilseeds by adding fertility, eating pests, cleaning up what’s left behind (chickens and pigs are extraordinary at this), eating weeds, and more.

This belief that land must only be used for vegetation or animals is silly and ignorant. Still, it shows the same mentality behind conventional agriculture, where it’s somehow “bad” to incorporate animals into raising crops. Most people see this as the “norm” for agriculture when it shouldn’t be, really.

Conclusions: Meme and Subsequent Ratio Debunked?

I’d like to hear your thoughts in the comments as to whether this has been debunked or not.

What’s clear is that a lot of misinformation was corrected. We found the source of this 16:1 statistic and discovered its author and originator had really flubbed up the numbers quite a bit.

Yet, we also found there’s plenty of ways to demonstrate how 16 pounds of grain to get a pound of beef (or, kilogram to kilogram… same shit different pile) can realistically be achieved. Whether that helps me in this debunking journey is yet to be answered.

We also found a lot of other misinformation related to this meme that I probably took too long and too much space to explain here. But I did it anyway.

This, quite honestly, was a fun post to create and to write. I’m sorry it’s a terribly long read but I hope you gleaned some things from it.

Thanks for reading and blessings to you.

~Karin

you miss a couple of key points to the debate. Although the math is good! Most cattle feeds are indigestible by humans Field corn is a perfect example. and most soy proteins is a by product. Cattle lots bring in all sorts of “trash food” such as vegetable waste, or almond hulls, etc. as protein sources. We can grown millions of tons of corn to feed livestock, but not millions of tomes of lettuce and other vegetarians delights. on the same land.

An excellent article. As a farmer in a very remote location, but with a deal of interaction with tourists I would love to be able to use this article with your permission. It is always nice to be able to present some more balanced views to people who are interested.